|

Ontario's Ontario's

first gold rush

by June Payne Flath

Gold is unique. It glows with an iridescence.

It will not corrode, rust or tarnish. It is malleable—some

say one ounce of gold can be drawn into a wire from 8 to 64

kilometres (40 miles long)—yet it is very dense, 19 times

heavier than water.

Canada is one of five countries that together

produce about 90 percent of the world’s gold. South Africa

leads the pack with the former USSR, Australia, the United

States and Canada following behind. More than half of the

Canadian output comes from the Pre-Cambrian Shield in northern

Ontario.

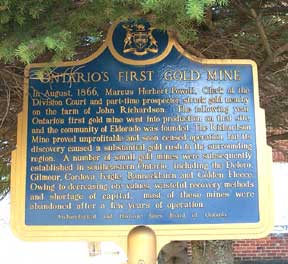

Ontario’s first discovery of gold

was declared on August 15, 1866, when 21-year-old Marcus Powell

in Hastings County spoke the words, “I discovered gold.”

Powell was trenching along a seam of copper on Richardson’s

farm when his pick broke through a cavity and opened into

a cave. The hanging wall was quartzite while the foot wall

was granite. The floor was iron, talc, quartzite, black mica

and other minerals, with gold leaves and nuggets found in

all these rocks. The largest nugget was the size of a butternut.

It took a while for word to get out, and

at first people didn’t believe him. But once the announcement

was made, a dozen mines and a collection of boom towns sprouted

from that rocky farmland near Belleville.

Madoc was the nearest town to the gold

fields, but only one stage ran from Belleville on the Grand

Trunk Railway. Getting to the gold rush site was as much of

a challenge as finding the gold. Four coaches and two covered

stages were brought into service. Prospectors picked up at

Belleville hotels at 7:30 a.m. were in Madoc by noon.

In the meantime, south of the discovery,

surveyor Charles Aylesworth got to work subdividing the northeast

corner of John Moore’s farm into 126 quarter-acre village

lots. Within weeks there were 80 buildings in the new settlement.

This boom town is Eldorado. Legend has

it that at the peak of the Hastings County gold rush, it cost

50 cents per night to sleep under a wagon in the vicinity

of Eldorado. Most gold-seekers chose to come to the established

town of Madoc, which swelled with service industries and hotels

eager to accommodate the influx of newcomers.

At least 26 roadhouses mushroomed between

Belleville and Eldorado. Excitement and population peaked

in April when it is believed that 4,000 prospectors, investors

and curiosity seekers arrived in central Hastings.

Land speculation was as lucrative as digging

for gold. Speculators bought and sold, price tags climbing

with each sale. Legend tells of one owner who sold 1 1/4 acres

of land for $700, only to learn that that same piece of land

sold for $4,000 an hour later. Those who weren’t selling

land or services were publishing books or giving lectures

on how to find gold.

One businessman, along with two American

sidekicks, was trying to stir up local investors for the Richardson

site. Richardson gave them a 30-day option on 19 acres of

land on his farm for $20,000 and allowed them to take several

barrels of rich ore as samples.

Richardson never saw any of the promised

money and so began another business deal with three other

men. These men paid him $36,000 in cash. Richardson immediately

gave young Powell $16,000 for discovering the gold. When the

first group of investors heard Richardson had gone elsewhere,

they took Richardson and the new owners to court. The courts

sided with those who had actually paid money for their deal,

and a building was erected near the main shaft and an armed

guard put on duty.

Rumours ran thick. One rumour claims the

guard did a lively business selling loose gold specimens.

Another claimed the mine was worthless and a “con”

to drive up land prices. Tension grew so bad between mine

owners and prospectors that a team of Mounties was sent to

keep the peace.

Before the Mounties arrived, 200 men marched

on the offices of the Richardson mine and confronted the manager.

They demanded to see gold, promising to pull the office down

around his ears if he didn’t comply. He let a few of

them into the mine and down into the gold cellar.

When these men returned to the surface,

the spokesman for the group climbed up onto a stump and declared

they were satisfied with the richness of the mine. They claimed

that from a quart of dirt they had washed $13 of gold. The

group gave three cheers and headed for a tavern.

Of 30 mine shafts only one-third showed

gold, and by 1870 even the mines that had been productive

were running dry. During the initial excitement, dozens of

mining companies were established by investors throughout

the gold region and beyond, including Hamilton, Toronto, Peterborough,

Belleville, Kingston and Montreal.

In July, 1867, the gold rush began a new

phase. Large companies entered the picture replacing individuals.

They brought with them large quartz crushers, steel sieves

and grinding pans that cost thousands of dollars. Two of the

stage lines between Madoc and Belleville withdrew their service,

and the Madoc hotels were no longer crowded. With fewer strangers

arriving, good bed and board accommodation was once again

easily obtained at a reasonable rate. The prospectors and

miners drifted away in search of new trails of gold dust.

This is an original story,

first published in The Country Connection Magazine,

Issue 51, Spring 2006. Copyright June Payne Flath.

RETURN

TO STORY INDEX

RETURN

TO BACK ISSUE PAGE

To purchase this issue of The Country Connection, please send a cheque to:

Gus Zylstra, 691 Pinecrest Road, Boulter ON K0L 1G0, Canada

In Canada: $4.95 + 2.20 shipping + .93 HST = $8.08

In the USA:$4.95 + 3.80 shipping + 1.14 HST = $9.89

|