|

Indentured

servants Indentured

servants

by June Payne Flath

It was an opportunity.

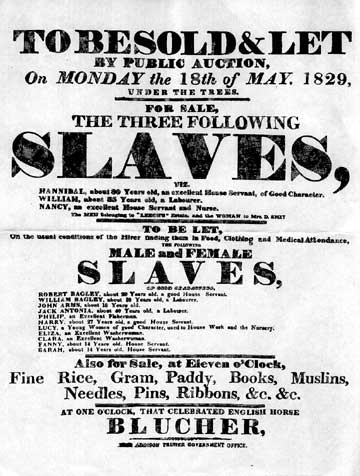

It was slavery. Some believe indentured servitude provided

passage to the New World. It’s been referred to as white

slavery as well as simply a business opportunity. Whether

it was a form of welfare or a chance to pay off debt depends

on the situation and whom you ask.

In the beginning, settlement of British

North America was not the goal. Early traders had a lucrative

business going with the natives and there was concern that

settlers might interfere. In time though Britain came to realize

the best way to protect this piece of prime real estate was

to populate it. That proved easier said than done. It was

costly to cross the Atlantic, and those who could afford passage

were not really the class of people needed.

Strong men were needed willing to swing

an axe all day, consider oxen their best friends and survive

winters on little food. Women who would tolerate such men,

not be opposed to swinging an axe and befriending oxen, would

also be welcome.

Farmers, blacksmiths, and innkeepers all

needed apprentices, people that would learn their skills and

carry them on. At the same time England, Ireland and Scotland

had swarms of unemployed due to the Industrial Revolution.

Their streets, poor houses, orphanages and prisons were overflowing

with homeless people. What to do with them was an ongoing

debate. Shipping them to the colonies was a solution for both

sides of the ocean.

Indentured labour was a form of contract

employment usually with a three- to seven-year time frame.

A person became an indentured servant by agreeing to work

off a debt during a specified term. “Debt slaves”

is another phrase to describe the arrangement, especially

in the case of prisoners and youth who had no choice and no

other opportunity to repay the debt.

Supporting a family was not only difficult

in the United Kingdom, it remained a challenge in the New

World. Since Ontario did not have “Poor Laws” (legal

obligation for municipalities to care for the local poor)

couples with a large number of offspring might make arrangements

for a child to be indentured.

A farmer unable to provide farms for all

his children might arrange to have one or more of them indentured

to a large local land owner. The agreement might include land

for a young man who worked to the completion of his term,

or domestic service for a daughter.

One estimate claims half of the white

settlers of North America were indentured servants. Destitute,

they agreed to work for the purchaser of the indenture upon

arrival in this foreign land. Jim Struthers, chairman of the

Canadian Studies Department at Trent University, says that

employers in Upper Canada used indentured servitude as a means

of maintaining a labour force. It was a legal contract that

held people to a particular employment, to a place, at least

long enough to pay back the initial cost of the passage. Some

contracts were similar to apprenticeships while the terms

of others were harsh. Some felt indentured servants were treated

worse than slaves. They only needed to keep the worker alive

for the term of the contract; if they died shortly after,

it was not their loss. Contracts varied from situation to

situation with no standard form. Permanent employment, a learned

skill, the promise of land, tools, any and all of these might

be promised for those who stayed for the duration of their

contract.

While women were in great demand in Upper

Canada, the only category open to a single woman who wished

to travel to Canada was domestic servant. Jane Ralston arrived

in Upper Canada in the 1850s at the age of sixteen. As the

daughter of parents too poor to care for her in a village

that offered no employment opportunities, she had been indentured

to a master in St. Thomas. Unhappy with her treatment in his

household, she ran away. Fugitive notices for runaway “white

slaves” were not uncommon; however, Europeans did not

stand out in a crowd, as did African slaves, and it was easy

for them to simply disappear. Jane made her way to Niagara

Falls and married Samuel Hall, a black fugitive slave from

the American south. Together they operated a hotel in the

Niagara Falls district and provided carriage transportation

for tourists.

“It was a way to provide for children,”

says Larry Hall, descendant of Samuel and Jane. He says while

they know little of how arrangements were made, they do know

that both Jane’s family and her master’s family

in St. Thomas had originated from the same village in Scotland.

“It was a widely used device in Great

Britain. They had a number of ways for getting rid of surplus.”

Eventually Upper Canada’s population

grew and businesses expanded, creating job opportunities,

reducing the need for indenture to ensure a work force. People

came as indentured servants, they stayed and their stories

are woven into the fabric of our history, our legends, our

lives.

This is an original story,

first published in The Country Connection Magazine,

Issue 50, Summer 2005. Copyright June Payne Flath.

RETURN

TO STORY INDEX

RETURN

TO BACK ISSUE PAGE

|