|

NIAGARA

FALLS: NIAGARA

FALLS:

A TREACHEROUS PLAYGROUND

by

Penny Gumbert

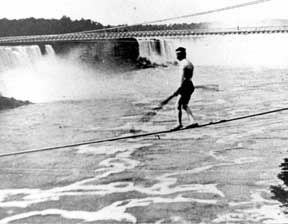

Stephen Peer, 1887.

Photo courtesy the Niagara Falls Public Library

During the retreat of Ontario’s last

ice age 12,500 years ago, torrents of water from the melting

ice ran from the upper Great Lakes, carved out the Niagara

River—actually a strait joining Lakes Erie and Ontario—and

poured over the Niagara Escarpment at what is now Lewiston,

New York. Father Louis Hennepin, the first man to write about

the amazing cataract in 1678 described the Falls as “frightful”

and that he “could not behold them without a Shudder.”

He wrote, “The Waters which fall from this horrible Precipice,

do foal and boyl after the most hideous manner imaginable,

making an outrageous Noise, more terrible than that of Thunder;

for when the Wind blows out of the South, their dismal roaring

may be heard more than Fifteen Leagues off.” Niagara

Falls is indeed a “thunder of water.”

The Great Lakes basin is the world’s

largest fresh-water system. Niagara Falls carries the water

from four of these Great Lakes into the fifth, Lake Ontario,

draining a total area of 684,000 square kilometres. There

are six cubic million feet of water going over the Falls every

minute—about one million full bathtubs. The American

Falls are 10 metres higher than the Canadian Horseshoe Falls,

but ours are twice as wide at 675 metres, with nine times

as much water falling. This downpour of water has its downside.

The Falls have moved 11 kilometres upstream because of erosion,

thus creating the Niagara Gorge. In 1969 the American Falls

were “dewatered” and its erosion studied by the

Army Corps of Engineers. No water flowed over the American

Falls that summer until autumn. The bottom line of the study

was that their falls were seriously eroding, but the engineers

chose to let nature take its course for fear of interfering

and making things worse. Erosion has slowed somewhat by the

diversion of water upstream for the generation of electricity.

Niagara Falls is not turned off at night,

though some people think so. However, the flow does vary.

The 1950 Niagara Treaty, the basis for determining the amount

of water that can be diverted for power generation, sets limits.

During daylight hours of the tourist season, the flow over

Niagara Falls must not be less than 2832 cubic metres per

second. At all other times it should be at least 1416 cubic

metres per second.

Niagara Falls hasn’t always been

a thundering waterfall, in fact, it once dried up. On March

29, 1848 there was barely a trickle. Mills relying on water

power fell silent, adding to the eerie hush. The curious were

drawn to the edge of the precipice to see fish and turtles

floundering on the dry river bed. The flow of water to the

Falls stopped for nearly 40 hours all because an ice jam was

blocking the river. Eventually the forces of nature released

the blockage, letting the waiting water crash through.

Chunks of ice and slush often try to form makeshift bridges

across the Niagara River below the Falls thus joining Ontario

to New York State (a risky attempt at unification). Years

ago, people used to toboggan on these slippery slopes, then

saunter over to booths to buy photos, curiosities and refreshments.

When a triple drowning occurred in 1912, the treacherous playground

was closed to the public.

FOR THE BRAVEHEARTED

Niagara Falls has been a questionable

challenge for some people. In 1827 a partially dismantled

schooner, the Michigan, was scheduled to go over the Falls

with a cargo of animals on board. Luckily, the ship broke

up before it reached the Falls giving the animals an escape

route before it went crashing over the edge. William Lyon

Mackenzie, then editor and publisher of the Colonial Advocate,

traveled from Toronto with his family to report on the incident.

On October 7, 1829 Sam Patch took the

plunge. Three times this funambulist walked out on a 40-foot

ladder projecting from Goat Island to leap over the Falls.

He wasn’t always so lucky. He drowned after leaping into

the Genesee River at Rochester, New York.

June 30, 1859 Blondin (John Gravelet)

walked along a tightrope stretched across the Gorge about

1200 metres below the Falls. He teased his audience by lying

down on the rope for frequent rests. To add to the drama he’d

motion to the Maid of the Mist far below, let down a twine

to retrieve a bottle of liquor, and satisfy his thirst before

throwing the empty bottle into the river below.

Ontario’s reigning pangymnastikonaero-stationist

was Bill Hunt of Port Hope (born in Lockport, N.Y.). This

multi-talented man, a painter, historian and inventor of the

circus cannon was married to Anna Muller, pupil of Franz Liszt

and niece of Richard Wagner. Maybe he had something to prove.

Known professionally as Guillermo Antonio Farini, Hunt repeated

many of Blondin’s feats. The dashing aerialist was not

content to just cycle across the Falls. While on the tightrope

he washed clothes, ate meals, and descended by rope onto the

deck of the Maid of the Mist after performing feats on the

perpendicular cable. Both Blondin and Farini’s managers

must have believed in their clients because they allowed themselves

to be piggybacked across the Falls.

In 1873 Henry Bellini bungee-jumped, taking

a flying leap into the Falls from his tightrope while hanging

onto a rubber cord fastened to the rope. On one jump the cord

came away, wrapping around his legs as he went under the turbulent

water. That was his last jump because the water was too cold,

he claimed.

Maria Spelterini at 23 years of age was

the first woman to perform on a tightrope at Niagara. The

report of her feat on July 8, 1876 was accompanied by photographs

showing her “attired in flesh coloured tights, a tunic

of scarlet, a sea-green bodice and neat green buskins.”

She often crossed with baskets on her feet. Typical woman—a

multi-tasker.

None of these danger-seekers ever lost

their lives while performing as did Stephen Peer, a young

man from Drummondville and assistant to Bellini. Successful

during his daytime crossings he tried it one night and drowned.

Reports vary as to the cause. Some say he’d been drinking.

Others assert his attempt failed because he was wearing street

shoes. Captain Matthew Webb, the first man to swim the English

Channel, died in an attempt to swim the rapids below the Falls.

His death marked the beginning of the era of the “barrel-cranks.”

The Niagara Parks Commission today prohibits

stunting, with a maximum fine of $10,000, but this isn’t

always a deterrent. In the last decade, 28-eight year old

Jessie Sharp, a white-water kayaker, attempted to kayak over

the Falls, with tragic results. He never showed for his dinner

reservation booked for that evening in Lewiston. An attempt

on a jet ski by 39-year old Robert Overacker failed as well.

As he reached the brink of the Falls, his rocket propelled

parachute failed to discharge.

Though there are about 500 waterfalls

higher than Niagara, its height and volume of water maintain

its stature as a truly natural wonder of the world—and

an Ontario heritage treasure.

This is an original story,

first published in The Country Connection Magazine,

Issue 47, Autumn 2004. Copyright Penny Gumbert.

RETURN

TO STORY INDEX

RETURN

TO BACK ISSUE PAGE

|