|

The

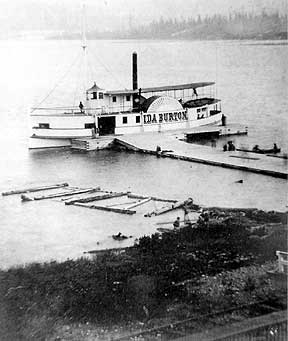

Ida Burton: The

Ida Burton:

Pride of Lake Simcoe

by Andrew Hind

It was not a romantic ending fate

dealt this elegant, historic vessel—the last side-wheeler

to ply its trade on the waters of Lake Simcoe.

The attractive wooden ship with large

paddle wheels midway from stern to bow, was built in an era

when steamship travel was nearing its end. But not only did

the Ida Burton go on to become one of the most successful

steamships of the day, the side-wheeler was the only one ever

built in Barrie harbour. Steamships were relatively easy to

build and did not require special dry-docks or slips, so communities

all around the lake—some, little more than villages—built

them.

Not a lot of facts are known about the

physical dimensions of this paddle ship, but the length was

between 100-110 feet—longer than 75-foot sister ship

Carrie Ella and much smaller than the 144-foot Emily May.

Sleek lines gave the Ida Burton a graceful appearance as it

cut through the water, but it was also a very sturdy craft

capable of sustained steaming at speeds averaging 12-15 miles

per hour.

In the mid-1800s waterways were the nation’s

highways until railways and roads spread across central Ontario.

Travel was economical, quick and relatively comfortable aboard

steamships crisscrossing Lake Simcoe ferrying mail, freight

and settlers to outlying settlements. They were vital to the

survival and growth of towns supplying farm goods and lumber

to railheads destined for distant markets. More than utilitarian,

they provided an element of romance to an otherwise difficult

era.

The pride of the Lake Simcoe fleet was

named after Ida, the beloved mother of Burton brothers James

Lindsay (1848 to 1910) and Martin (1852 to 1914). The two

men were among the most prominent businessmen in 19th century

Barrie. Together they had a hand in most of the large industries

in town and owned nearly half of the nearby Village of Allandale

(now engulfed by Barrie). James Lindsay (J.L.) occupied most

of his time with the Northern Navigation Company, whose fleet

steamed across the waters of Georgian Bay, Lake Simcoe, and

Lake Couchiching, delivering mail, cargo, and passengers.

Because Barrie wasn’t a major port,

or even a particularly notable community until mid-century,

the Ida Burton was the only side-wheeler the Burton’s,

or anyone else, ever built there. Trains had cornered the

shipping market by the time the rails reached Barrie in the

early 1850s. The town lost its reliance on water transportation,

but other communities not directly reached by rail continued

to build ships.

For nearly a decade, from 1866 to 1875,

the Ida Burton left Barrie harbour with train travelers from

Toronto bound for luxury hotels on the Muskoka Lakes. First

stop Orillia, then full speed ahead across the length of Lake

Couchiching for connections with Northern Railway. From this

railhead at Washago, on the Severn River, weary travelers

once again rode the rails until Gravenhurst where they boarded

a final steamer.

The Ida Burton was hired for private functions

at a time when the temperance movement was making headway

in reducing alcohol sales in Ontario. Consuming alcohol was

often frowned upon, especially among the well-heeled, “upstanding”

citizens. Private excursions aboard the Ida Burton were rarely

dry, used instead as opportunities to indulge in alcohol away

from prying eyes. Parties, complete with musical entertainment,

were often the highlight of the summer social season—along

with the occasional cancelled wedding.

One day a strapping lad by the name of

Jimmie Reid was about to marry, the ceremony mere hours away.

Everyone was decked out in their finest, eagerly anticipating

the nuptials. Suddenly, a gasping friend raced up to the anxious

groom. The wedding had to be called off! The bride, Nora McGlashen,

was Irish on her mother’s side! Scotsman Jimmy Reid agreed;

union with an Irish lassie was completely unacceptable. He

broke the news to the assembled guests. There would be no

wedding today! All dressed up with nowhere to go, many of

the guests—and reputedly the groom as well—decided

to have a party anyway. By all accounts, it was a raucous

affair aboard the Ida Burton where whiskey and good times

flowed. Not so amused were fellow passengers, the Sons of

Temperance, advocates for abstinence from drink.

Such heady days could not last forever.

Roads improved and railways snaked north. Operators tried

to make a living offering luxury cruises to tourists, but

competition was fierce. The final blow was dealt from a new

source—the Muskokas. As the area opened, it catapulted

up the list of vacation spots in Ontario and conversely, steamers

disappeared one-by-one from Lake Simcoe.

In less than two decades after the launch

of the Ida Burton, railways had stretched their web from Toronto

to Gravenhurst. Steamships and similar vessels were left to

rust. With its primary income gone it was only a matter of

time before the Ida Burton went to a watery grave alongside

so many kin.

The inevitable came in 1876 when the ship,

stripped of machinery, was unceremoniously sunk along the

Orillia shoreline. Though the once elegant side-wheeler ended

up as foundation for a wharf, it will always be known as the

Pride of the Lake Simcoe fleet.

The steamship’s passing was little

more than a minor setback for the Burton brothers who went

on to help found the Barrie Electric Light Company. Martin

also went into the lumber business in a big way. With extensive

timber rights and a huge mill at Byng Inlet along Georgian

Bay, he became one of the wealthiest lumber barons in Ontario.

J.L. devoted much of his later years to local politics, spending

many years as deputy reeve of Barrie and reeve from 1889 to

1890.

This is an original story,

first published in The Country Connection Magazine,

Issue 45, Spring 2004. Copyright Andrew Hind.

RETURN

TO STORY INDEX

RETURN

TO BACK ISSUE PAGE

|